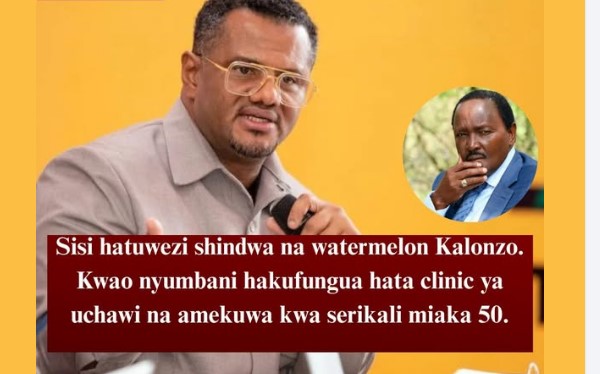

Former Mombasa Senator Hassan Omar has launched a sharp attack on Wiper Party leader Kalonzo Musyoka, using ridicule to question both his political strength and development record. In a mocking statement, Omar dismissed Kalonzo as politically weak, sarcastically referring to him as “watermelon,” a term often used to imply indecisiveness or double standards, while also accusing him of failing to deliver tangible development despite decades in government.

Hassan Omar’s remarks center on a long-standing criticism frequently directed at veteran politicians: longevity in leadership without visible impact at the grassroots. By claiming that Kalonzo failed to establish even basic facilities in his home area, Omar sought to portray him as a career politician whose years in power have not translated into meaningful change for ordinary citizens. The exaggerated reference to “miaka 50” was clearly intended to reinforce the narrative of overstaying in leadership.

The use of mockery rather than policy-based critique reflects the increasingly combative tone of Kenyan politics. Insults and sarcasm have become common tools for discrediting opponents, especially as political alliances shift and competition for public attention intensifies. In this case, Omar’s statement appears designed more to entertain and provoke than to invite substantive debate.

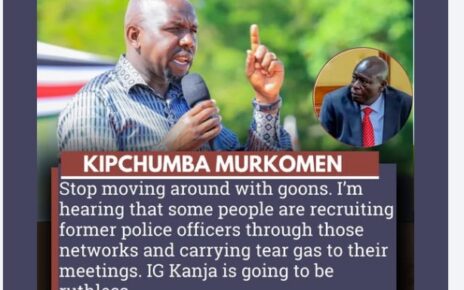

Supporters of Hassan Omar argue that public figures who have enjoyed long political careers should be subjected to tough scrutiny. They believe voters have a right to question what leaders have accomplished with the power and opportunities they were given. From this viewpoint, harsh language is seen as a reflection of public frustration with leaders perceived as recycling promises without delivery.

On the other hand, Kalonzo’s allies view the remarks as disrespectful and misleading. They argue that reducing a long political career to insults ignores the complexities of governance, coalition politics, and shared responsibility in government. They also contend that personal attacks distract from serious discussions about policy, national unity, and economic recovery.

The exchange underscores a deeper struggle within Kenya’s political landscape, where experience is increasingly framed either as wisdom or as failure, depending on who controls the narrative. As the country edges closer to another election cycle, such verbal clashes are likely to escalate, with leaders and their allies using sharp rhetoric to shape public perception.

Ultimately, Hassan Omar’s mockery of Kalonzo Musyoka is less about clinics or years in office and more about political positioning. It reflects a broader contest over credibility, relevance, and legacy—issues that will continue to dominate Kenya’s political discourse as leaders battle for influence and voter trust.