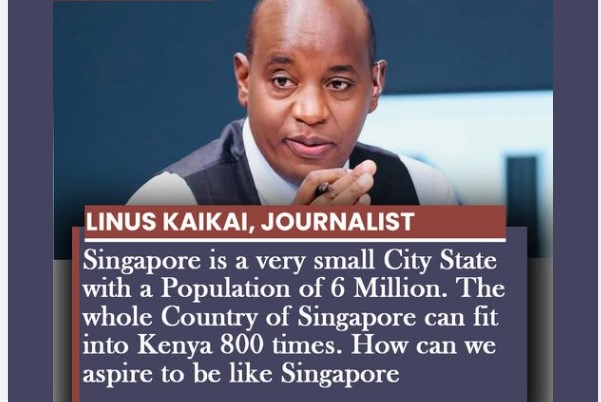

Linus Kaikai’s question—how Kenya can aspire to be like Singapore despite Singapore being a tiny city-state of six million people—raises an important national debate. At face value, the comparison seems unrealistic. Singapore could fit into Kenya hundreds of times, has a much smaller population, and operates as a single, highly controlled urban unit. However, history shows that national success is not determined by land size or population alone. What truly separates Singapore from countries like Kenya is governance, discipline, and institutional strength.

Singapore’s transformation did not come from geography or natural resources. In fact, the country has almost none. Instead, its success was built on strong leadership with a clear long-term vision. From independence, Singapore’s leaders focused on building an efficient state, prioritizing national interest over personal or ethnic gain. Policies were designed to last decades, not election cycles. Kenya, on the other hand, often shifts direction with every new administration, disrupting continuity and weakening development outcomes.

One of the strongest pillars of Singapore’s success is the rule of law. Laws apply equally to everyone, regardless of status or wealth. Corruption is dealt with swiftly and decisively, sending a clear message that public office is a responsibility, not an opportunity for personal enrichment. In Kenya, corruption remains deeply entrenched. Investigations take years, prosecutions collapse, and public confidence in accountability institutions remains low. This difference alone explains much of the economic and social gap between the two countries.

Singapore also invested heavily in human capital. With no minerals or vast agricultural land, it focused on education, skills development, and innovation. The education system was aligned with economic needs, producing a disciplined and highly skilled workforce. Kenya has enormous human potential, especially among its youth, but this potential is weakened by underfunded education, skills mismatch, and limited investment in research, technology, and manufacturing.

Another key lesson from Singapore is institutional efficiency. Public service delivery is fast, predictable, and largely free from political interference. In Kenya, bureaucracy is often slow, politicized, and inconsistent. Projects stall not because of lack of money or ideas, but because of inefficiency, duplication, and poor coordination between government agencies.

Importantly, Kenya does not need to transform its entire territory to Singapore’s level overnight. Singapore itself is a city. Kenya can start by developing world-class cities and economic zones. Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, and planned developments like Konza Technopolis can be governed with strict planning, reliable infrastructure, efficient transport systems, and strong law enforcement. These cities can then drive national growth, just as Singapore’s city-state model drives its economy.

Urban planning and discipline also play a major role. Singapore enforces zoning laws, traffic regulations, environmental standards, and public order without compromise. In Kenya, good policies exist, but enforcement is weak or selective. Disorder, illegal developments, and infrastructure strain are consequences of governance failure, not population size.

Ultimately, Kenya should not seek to copy Singapore exactly. The two countries are different in history, culture, and structure. However, Kenya can adopt Singaporean principles: meritocracy, accountability, long-term planning, respect for the rule of law, and zero tolerance for corruption. These principles are transferable to any country, regardless of size.

The real question, therefore, is not whether Kenya can be like Singapore in scale, but whether Kenya can choose seriousness in governance. Size did not make Singapore successful. Choices did.